Indeed, Arkham Asylum evinces not so much the monomythic Hero’s Journey as it does a highly specific character assassination of what Morrison would later call “the ’80s interpretation of Batman as violent, driven and borderline psychopathic.” The introduction via flashbacks of Amadeus Arkham – founder of the asylum where Batman’s most disturbed (and most disturbing) nemeses are interred – is yet another red herring, distracting readers from the realization that Morrison’s tale is far from some universal parable about the nature of madness nor is it an attempt to plumb the depths of the everyman’s soul. In selecting Batman as the book’s hero, however, Morrison attempts a narrative sleight of hand. By contrast, the supposedly “serious” Arkham Asylum fashions itself, as it does its version of the Joker, as “super-sane” – that is, as a serious, sober reflection of what the Joker’s psychotherapist calls “the world as a theatre of the absurd.” The subtitle also suggests Arkham Asylum’s conscious opposition to what DC had in years past called “Imaginary Stories.” Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, such stories were typically one-off tales about possible realities (such as one comic in which Superman revealed his secret identity to and subsequently married Lois Lane), stories that would have no bearing on the ongoing continuity of the DC universe.

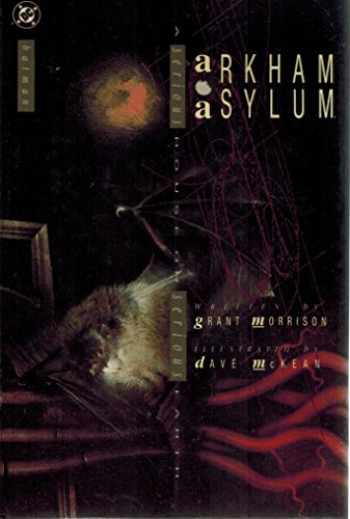

The subtitle of Grant Morrison and Dave McKean’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth is quoted from the English poet Philip Larkin: “A serious house on serious earth it is, / In whose blent air all our compulsions meet, / Are recognized, and robed as destinies.” Larkin was writing about churches – serious places where serious questions might be asked about man’s place in the universe – and the reference seems fitting for a tale so rife with religious imagery and which outwardly appears to interrogate the nature of its hero’s existence.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)